Rubik's Cube

| Part of a series on |

| Spatial Puzzles |

|---|

|

The Rubik's Cube is a puzzle toy invented by Hungarian sculptor Ernő Rubik in 1974. In 1980, the toy was first sold internationally, resulting in a boom in popularity that became a full-blown craze in less than a year. Today, it's still extremely popular and has spawned many variations that make solving it easier, more difficult, or simply a bit different.

Most modern versions of the original cube have 6 colored sides, using the colors red, white, blue, orange, green, and yellow, with the entire cube being made up of 26 visible 'cubelets'. To properly solve it, one must twist faces of the cube so that all faces contain a single color, dictated by the immobile centre cubelets.

Background[edit | edit source]

History[edit | edit source]

Ernő Rubik first developed the Cube while working as a professor of architecture at the Academy of Applied Arts and Crafts in Budapest. At the time, he considered it an experiment in structural integrity, attempting to achieve the individual moving parts seen in the final product without the structure simply falling apart. When he had accomplished this (having colored the sides at some point along the way, he reportedly scrambled the cube and attempted to solve it, only then realizing the puzzle potential of the device. He filed a patent for it in 1975, calling it a 'Magic Cube'. The Cube sold well in Budapest, and was eventually brought (with Rubik's permission) to the 1979 Nuremberg Toy Fair by businessman Tibor Laczi, where it got the attention of Tom Kremer (founder of Seven Towns Game and Toy Invention). After making plans with the company Ideal Toys to introduce the Cube to an international market, a name change was made to make the toy more recognizable, solidifying 'Rubik's Cube' as the official name.

The release of the Rubik's Cube outside of Hungary sparked a craze, particularly in France, the United States, and the United Kingdom. This craze lasted for about 2-3 years, spawning the first (and only, until 2003) speed-solving world championship in 1982, as well as several guidebooks, an art installation at the MoMA, and a short-lived animated TV show called Rubik, The Amazing Cube. Sales ended up plummeting between 1982 and 1983 (long before Rubik, The Amazing Cube aired, possibly contributing to the show's failure), and most newspapers declared the craze over by late 1982.

The 21st century brought a resurgence in popularity to the Rubik's Cube, with sales skyrocketing out of nowhere between 2001 and 2003. In addition, the first World Championship since 1982 occurred in 2003 in Toronto, bringing the competitive scene back almost immediately after the popularity rose. This resulted in (among other things) the formation of the World Cube Association (WCA) in 2004 to handle all official competitive cubing events going forward. Since then, the World Championships have occurred every two years, with the exception of 2021's cancellation due to COVID-19.

Variations[edit | edit source]

Since its widespread acceptance by the toy and puzzle community, many variations on the original Rubik's Cube have been invented. Some have been successful, finding places in events like the Rubik's Cube World Championships, but others haven't been so lucky. The ones that are currently accepted by the World Cube Association as event-worthy are:

- Pocket Cube (2x2x2)

- Rubik's Revenge (4x4x4)

- Professor's Cube (5x5x5)

- V-Cube 6 (6x6x6)

- V-Cube 7 (7x7x7)

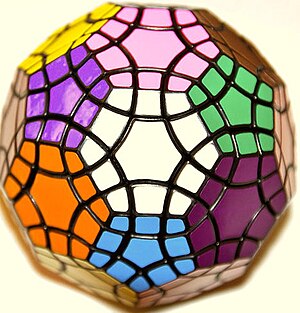

- Megaminx - A dodecahedron-shaped puzzle whose faces have stars on them.

- Pyraminx - A side-length-3 pyramid-shaped puzzle that has a maximum solution length of 11 twists.

- Rubik's Clock - A flat puzzle consisting of 18 clock faces that can be turned in combination, with the goal to set all of them to 12:00.

- Skewb - A cubic puzzle with diagonal rotation rather than horizontal and vertical rotation.

- Square-1 - A cubic puzzle that inplements horizontal, veritcal AND angled rotation, resulting in shuffled cubes that no longer look like cubes.

Other variants do exist, such as the spherical Rubik's 360, the flat Rubik's Magic, and the truncated icosahedron-shaped Tuttminx (among others), but while they have found varying levels of success in the toy market, they are not currently run in official WCA competitions.

Puzzle Application[edit | edit source]

TO DO

Strategy[edit | edit source]

Identification[edit | edit source]

Outside of puzzles that provide physical Rubik's Cubes to solvers, determining whether a puzzle involves them can be a bit tricky, but can almost always be helped by clues within the puzzle. As Rubik's Cubes have consistent coloring, the use of those colors (red, white, blue, yellow, green, orange) and only those colors is often a good indication of their use. This is especially true when one considers that very few other topics use that subset of colors (and those that do include them often include others, like many video game rarity systems also including purple).

Another common clue is the presence and repeated use of the letters commonly used in solving guides/algorithms to represent the different faces (L/R for Left/Right, U/D for Up/Down, and F/B for Front/Back). Similarly, directions indicating these things, or relying heavily on turns of any sort should be treated with suspicion.

Of course, sometimes puzzles will be much more obtuse and simply be about or heavily reference cubes. In these cases, there's a not-insignificant chance that Rubik's Cubes (being perhaps the most famous cube) will become relevant, if not actively being the core conceit of the puzzle. This is especially true for any 3x3x3 cubic structures.

Solving[edit | edit source]

As the Rubik's Cube has been around for decades, there's been quite a bit of time for people to develop strategies and algorithms to flawlessly solve shuffled cubes. These can sometimes be very helpful for solving cube-based puzzles, particularly if they involve actual, physical cubes. However, a more common topic of Rubik's Cube puzzles is shuffling a cube in a certain way from a solved state, in which case these algorithms are less helpful. Instead, visualizers (or actual, physical cubes if solvers can get their hands on one) are much more helpful.

TO DO

Notable Examples[edit | edit source]

Virtual Cubes[edit | edit source]

- Covert Tops (MITMH 2014) (web) - While technically involving a real cube, solvers were not shown it nor were they given one to work with. Instead, they're shown the hand movements of someone twisting a cube behind the cover of a camera, forcing solvers to try and recreate the hand movements they do see on a virtual cube (or a physical one of their own).

- The Dining Philosophers (GPH 2022) (web) - Part Conundrum, part ordering logic, and part Rubik's Cube puzzle. At certain points of this puzzle, solvers are given sequences of twists to perform on a solved Rubik's Cube. If ordered correctly, each of the sub-puzzles should result in Click to reveala cube whose front face resembled a world flag.

Physical Cubes[edit | edit source]

- Cubology (MITMH 2002) (web) - Solvers were given a Rubik's Cube with letters written on each face. The twist was that Click to revealone piece had been removed and replaced upside-down, making the entire cube unsolvable. If solvers realize this, they can proceed to the actual puzzle: taking the whole thing apart and sort the pieces by overlapping colors/letters to get a new message.

- Cube (MITMH 2015) (web) - Solvers were given a black-and-white Rubik's Cube, with lines and letters appearing on each face. The 'solved' state was one where Click to revealone could follow the line continuously across the cube, reading a message as they go.

As a Theme[edit | edit source]

- Erno Rubik (MITMH 2013) (web) - Fittingly, a round themed around the creator of the Rubik's Cube is actually themed around the Cube itself. The round even had a virtual cube to play with, and each cube represented a puzzle. The middle cubes for each face represented a meta for that round, using all of the answers that contained a piece of that face, resulting in a lot of Multi-use Answers.

- Edric's Truzzle Hunt 2022 (web) - This whole hunt actually takes place on a giant Rubik's Cube, with four puzzles per face. When solvers reached the end of the hunt, they were faced with Click to reveala now-scrambled cube that they had to deal with in order to finish out the hunt.